When I arrived in Memphis, I had just dropped out of college and found a temporary sublet in a friend’s apartment on Poplar Avenue. The city felt glamorously run-down, like an Eden of the South, ravaged and plundered by Sin herself. The streets smelled of sour mash and slow-cooked meats. It was springtime. The dogwoods had bloomed in full; waves of rich, dense air wafted in off the Mississippi. The friend I was going to live with was Arienette Allistaire—and yes, she was exactly as melodramatic, suspicious, and gorgeous as that sounds. The name suited her, frankly, though I always wondered if the name fit her, or if she had designed herself to fit the name.

A. leased an apartment in a four-story monstrosity called The Turing House. The Victorian house had been haphazardly divided up to house multiple tenants. Her place, our place, had a kitchen with no stove, a bathroom with no sink, and one bedroom with a bathtub in it. The sunroom, which was mine now, was about the size of a breakfast nook. In fact, maybe it was a breakfast nook. Your guess is as good as mine.

I didn’t know what it meant to be on my own then; it was my first time living far away from my family. I stapled floral bed sheets over the windows and fashioned a bookshelf out of cinderblocks and plywood. I slid my twin mattress into a corner, upturned a plastic bluemilk crate for a nightstand, and stacked a tower of duffle bags to hold my clothes.

That night I left the apartment around ten to pick up supplies for the week. I was in my car with the windows down. At a red light, I glanced over at the car to my right—it was a big dirt-colored Buick. A grisly middle-aged man in the driver’s seat stared at me, his gaunt face lit red by the stoplight. He didn’t have a left ear.

Without breaking eye contact, he took a swig from a beer bottle, held it high out of his window, and hurled it down at the road between us. The sound reminded me of when my stepmother slammed the door so hard the small glass window at the top of it shattered. I watched the guy, frozen, waiting for him to make the next move. A diabolical green glow appeared on his face. With his palm he blew me a big kiss and sped off.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

We met on a Greyhound heading back to Nashville from Chicago. I can’t remember exactly when, but I know it was cold outside. She meandered down the carpeted aisle of the bus, black jeans, camouflage jacket. I couldn’t take my eyes off of her. I could faintly hear a Modest Mouse song leaking from her headphones. The iPod in her hand, which was tiny like a deck of cards, seemed alien and cool. I had a portable CD player that skipped every time the bus hit a pothole. She was tall, commanding, nearly unapproachable. Everything I was not. She sat down next to me and somehow, after a few too many seconds, I mustered up the courage to speak. I was terrible at initiating conversation with strangers, especially other girls, especially cute ones. In that moment, some inner force shoved me blindly over the cliff.

-So, where are you headed? I said.

-The land of soul and swine, she said.

I didn’t know what that meant, but after an hour of small talk, I deduced that she was referring to Memphis. We talked the whole ride—about music, conspiracy theories, transgender people, and the best type of macaroni and cheese. Her brain was an arsenal of obscure knowledge and nearly unbelievable stories. I wondered a few times if she was lying about some things, but then I thought: Why would she? I’m no one. The bus made a late night stop in Louisville and we ate dinner at a Wendy’s attached to a big gas station. We ordered the same thing and I discovered we both dipped our fries in chocolate Frosties, which seemed romantic and profound at the time. Sometimes, when you feel crushingly alone in the world and you’re on a bus full of strangers, the tiniest connection to another human can feel like lightning. I watched as she dipped a fry into her cup of frozen sludge and I realized I never wanted to be apart from her. I had been asleep my entire life, it seemed, and I was just now waking up. It was a quiet love and it was all in my head, but the feeling enveloped my body like a warm wave.

When I debarked in Nashville, we exchanged numbers and emails, and I saw to it that we stayed in touch over the next couple of months. In my mind, A. was a sugar rush, a jazz song, a magic trick. She was a new planet entirely. I thought about her all the time after that, imagining how my life would be different if she had a starring role in it. It would be like living in a Godard film all the time: understated, sexy, profound. So naturally, on the day all the horrible shit went down with my stepmother, the day I was forced to leave my parents’ house, A. was the only person I called.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

My third night at the apartment, A. called me late at night. I didn’t know where she was calling from.

-Ya wanna rake coals tonight? she said.

-Rake coals?

It seemed like I never knew what A. was talking about. She used certain words, her words. She had a language unto herself: one, I presumed, she had pieced together from years spent slinking around the underground.

-Look, I made half-a-grand off a group of waldos last night. Got an eight ball. Let’s go to the scopes.

-I need to be in bed early, job interview in the morning, I said.

-You can sleep when you’re dead, asshole. I’m on my way to pick you up. Wear something ugly.

She hung up. That was another thing, A. was always advocating for unflattering, unstylish clothing. She said it made people more free to be themselves. I went along with it because she was my friend, and because, as it turns out, she was kind of right.

Driving in my car, we were coming toward something. It was a cloudless night in August and A. was seething with energy like a just-lit bottle rocket. She cut the headlights and we sped in the dark down a dirt path. She slammed on the brakes. I could barely make out a group of people standing in the middle of an open field.

-Where are we? I asked.

-You’re gonna love this, she said, nodding her head.

She pulled out a bag of cocaine, dipped her car key in it and held it under her nose. She breathed in deep, handed me the bag and key and I did the same. She tilted her head way back.

-First class, she said. We’re flying first class tonight.

In the middle of the field were four giant telescopes that looked like cannons ready to fire at the sky. Beside each one stood its owner talking to people about whatever the telescope was focused on.

-See the two blue dots? Those are kissing stars.

-I see, one girl said.

-They’re young stars, very hot and bright. One day they’re going to swallow each other whole.

-What do you mean?

-They’ll keep getting closer, and will eventually collide. We may not be around to see it. That collision can go one of two ways: they’ll become one giant star or they’ll become a black hole. If the one on the left is anything like my wife, it’s sure to be a black hole!

A. made her way to the eyepiece to see the kissing stars.

-Ruthie, you must! They’re like cells frozen in mid-divide, she said.

I looked in to see the two fiery blue bodies touching each other.

-Star crossed lovers, the man said. One hundred and sixty thousand light years away.

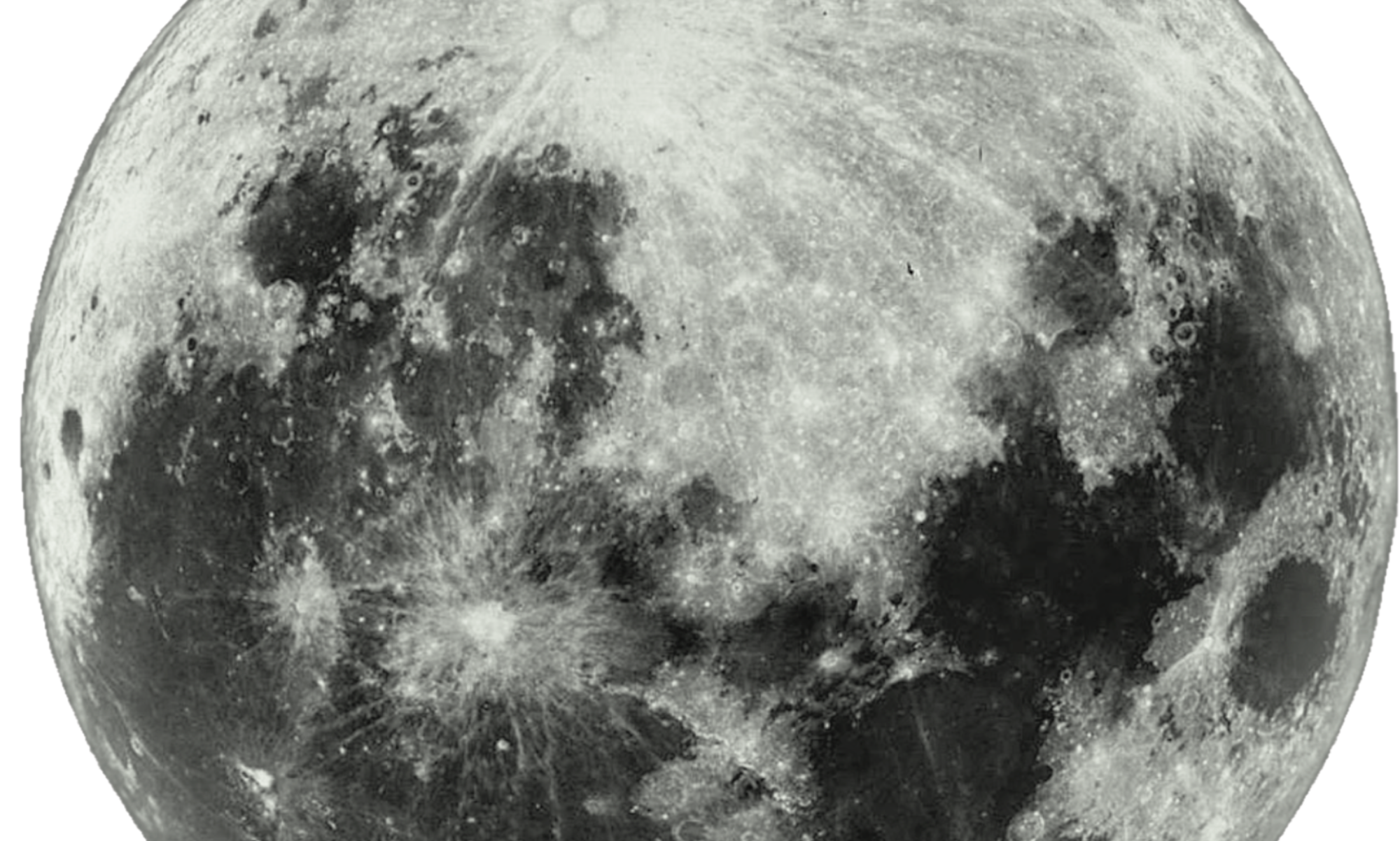

In the other telescopes, we saw more stars, the moon, and the Milky Way. Back in the car, A. started talking very fast.

-Isn’t it insane that what you see in a telescope isn’t that different from what you’d see in a microscope? What comes out on the other side isn’t so different. What do you think that means? I feel like there’s something to it all.

-I don’t know, I said.

I pressed my cheek against the cool car window. She drove out of the field with the headlights off.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

After three months of living together, our lives had become tightly enmeshed. We were one organism patched and bonded together. Everything we owned came from second-hand stores or dumpsters or sidewalk sales. Our apartment was a piecemeal collage of a thousand homes that came before it. Same went for our clothes. We wore work shirts with names like Martin and Eddie on the front pocket, threadbare mom jeans, overalls, stained kitchen aprons, orthopedic shoes. We carried our things not in purses, but in bowling ball bags and briefcases that barely latched. We were a walking museum of the American working class. We were a force to be reckoned with.

On a windy Friday night just before Halloween, A. came home from Christie’s Cabaret with a black eye and blood streaming down her cheek. I took it for a prank, but when she held her gaze to the ground, I realized I was wrong. I leapt off the couch and ran over to her.

-Who did this?

-You should see the other bitch, she said.

-Seriously, what happened? I said.

-Bones fired me.

-He hit you?

-It was self-defense.

-You hit him?

-He fired me!

-Why?

-I guess because I hit him.

-Why’d you do that?

-He tried to bogart the rest of my stash when I was on stage, that weasel prick!

-Huh?

-Play with fire, you get burnt, baby.

-Who or what is the fire in this scenario?

-I’m always the fire, Ruthie, always.

That was all the information I could get about why A. got fired from Christie’s. After that, she bottomed out for several weeks, binge-watching CSI and Law & Order. She didn’t shower for days, sometimes a week. If she ate at all, it was a midnight call to Golden China. I assumed she’d get back on her feet pretty quick, but she didn’t work for a long time. Apart from the occasional coke or molly deal, she stopped making any money at all.

One night I found her lying on her back in the kitchen staring up at the ceiling.

-What’ve you been up to today? I said, trying to sound casual.

-Watching a thousand dust particles swim upstream in the sunlight.

I stayed silent.

-I filmed it with my camcorder, it was nice. It felt like an honest moment, she said.

-What are you going to do with it?

-I’m thinking it’s going to be a short film. Dust is mostly human skin, so if you really think about it, it’s like a thousand little ghosts swimming in the sunlight. Isn’t that nice?

-That is nice. Our apartment is covered in little ghosts.

-Yes, human soot, she said.

-That’s nice.

Back in the sunroom, I imagined the two of us collaborating on films and paintings and poems, becoming a famous art duo storming the gates of the Guggenheim in our ugly clothes and wild spirits. I liked the idea a lot.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

I took a job as a cocktail waitress at a Beale Street nightclub. The place had a mean bouncer and four floors, each with a different style of music. There was a salsa lounge and a jazz bar. I worked the ground level dance club, which was the most crowded of all. My shift started at 6 p.m. and ended at 5 a.m. In my regulation plaid mini-skirt and tight tank top with the club’s logo displayed prominently across my breasts, I walked around all night taking drink orders from roving clubbers and trying to balance too many cocktails on a tray the size of a Frisbee. It was shit work, but it paid well.

After work, I would meet up with A. at our favorite spot, Zeke’s. Practically everyone in Memphis worked late, so we all ended up socializing between the hours of 11 p.m. and 3 a.m. When the standard bars closed, there were all these secret after-hours spots that served drinks until 6 a.m. They operated under a tacit agreement that, at any given moment, the cops could just bust in and arrest everyone in the building, no questions asked. In Zeke’s eight years of business, there had been two such raids. A. and I considered that decent odds, so we took our chances.

One morning as we were leaving Zeke’s, the sun peeking up over the horizon, a kid, maybe ten or eleven years old, ran up and pointed a gun at me.

-Gimme yer money! And that phone.

He had a squeaky voice, and his hands weren’t shaking at all. A. lurched back.

-Whoa, tyke! You don’t have scratch like this. Put that thing down, she said.

The kid yelled something I couldn’t understand and gripped the weapon tighter. I reached in my back pocket and pulled out the thick wad of tips I’d made at the club that night. $386 in ones and fives. The kid beamed like a Cheshire cat. I thought fireworks were going to shoot out of his ears.

I stood there and imagined the boy running all the way home, bursting through the screen door of a clapboard house in Orange Mound where his big brother and all his big friends would be sitting around a kitchen table weighing bags on scales. The kid would hand over the stack of money, the most he’d ever scored, and his big brother would praise him for what a good job he did. Get it how you live, the brother would say, sunny and high-fiving the boy’s little hand. And there it would be: the rest of all time. People weren’t bad because they wanted to hurt other people, they were bad because they wanted to please them.

-Don’t give this nematode our money, A. whispered sideways.

-Our? I said.

Just as I handed him the money, A. made a sudden swat for the kid’s gun and knocked it out of his hand.

-Cunt! the boy squeaked, scrambling for the gun.

He scooped it into his jacket and took off, the stack of money bulging between his little hands.

A. and I were silent all the way back to our cars. I felt like an earthquake walking down the street.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

I can’t recall how A. convinced me to dance for the first time, but I remember it was around the holidays. We were dead broke. I was down to working just one night a week at the club.

-You’d slay at stripping, you know, A. said one cold afternoon, yelling at me from the kitchen.

I walked out of my room and found her sitting in a shadowy corner chair, a Faulkner book in her lap, a cigarette dangling from her lips. She looked like a professor on death row.

-Not a chance in hell, I said.

-$400 an hour is no small potatoes.

-Look at me, I pointed to myself.

She scanned me from head to toe.

-You’ve got every part you need, she said.

I auditioned for Christie’s on a Wednesday afternoon. The winter sun was shining bright when I pulled into the South Memphis parking lot. Christie’s looked inconspicuous and deserted. It had mirrored windows, no signage, and was attached to a Subway. I sat in my car and watched office workers dust breadcrumbs from their khakis as they walked back to their cars. They were laughing and waving to one another.

When I walked in the front door, it was dark and nobody was there. I started to panic. I wanted to leave. It wasn’t too late. I could just walk right out the door, I thought. I could go home. I could make stir-fry. I could finish Infinite Jest like I promised myself. I could call that guy Austin back. I could go to the zoo and talk to the giraffes. I could do an infinite number of things that are not this. A woman near the coatroom stopped her vacuum and looked at me.

-Hello? she said.

-Hello. Hi, I’m looking for Bones? I said.

-You work?

-Well, I’m trying to. I guess. Do you know where he is?

-No, sorry. Maybe there?

She pointed down a long dim hallway. Just then a woman with a clipboard stormed into the lobby.

-You! Come with me.

She had a thick body and a face like a bulldog. Her diaphanous purple blouse billowed behind her like a superhero’s cape as she zipped down the halls. She took me to a room and told me to change clothes into a microscopic blue dress that she threw into my arms and to tie my hair back. The room was frigid and smelled like lemons soaked in gin.

-You got heels? she asked.

I stared blankly at her, and looked down at the yellow work boots A. and I purchased from Citi Thrift just days before.

-No, I said meekly.

-Well, you’ll have to make due.

I put on the tight blue dress and looked at myself in a cloudy full-length mirror fastened to the back of the door. I looked like a photo of a toddler parading around in her father’s oversized shoes. I was more teenager than woman, and it was painfully obvious.

When I came out of the room, the caped woman led me into a dark vestibule.

-Just stand here and be quiet, she said. When they call your name, go through that door. Don’t say anything, no speeches, no monologues, just get up there. Listen for the queue, and do your routine. Nothing you say will help your chances. We’ve had way too many girls preaching lately. Trust me, you’re better off keeping your mouth shut. Remember, beauty is about energy, not words.

She left. I waited nervously, dying inside just a little more each second. A froggy voice came over the intercom.

-Ruthie…Tichnor? the voice said. Oh wow, gotta to do something about that name. Okay. Ruthie…Tichnor. Jesus.”

I went through the door like I was told. I felt like a marionette being controlled by a stranger whose hands looked a lot like my own. I was wearing a tight blue dress and heels that hurt. I walked out onto a stage that was lit in the color of forgotten love. I moved my body like a person who wasn’t me, the funky dance music pounding through the crackling speakers. The only thing I could think of the entire time was my grandmother’s voice as she consoled me the year I didn’t make the cheerleading team when I was fourteen. I was certain my life was ruined and she cooed into my ear as she rocked me back forth, Everything is waiting for you, she whispered. Everything is waiting for you.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

The next morning, a man named Lucius called to tell me they were impressed with my performance and would like to offer me a weeknight gig. The room started to spin. I hung up on him and got sick in the bathroom. That was the beginning and end of my dancing career. When A. asked me about it the next day, I ignored her.

I feared running into Bones or Lucius or the other men I danced for, so I didn’t go out much the rest of that winter and most of that spring. I guess it was around that time I cultivated an addiction of my own inside the curtained walls of my sunroom. Opium, speed, hash, whiskey, I’d take whatever I could find, but I liked cocaine best of all because it helped me not to feel so small. That was, of course, before I understood that learning how to be small was what life was all about.

Occasionally A. and I would find ourselves both awake at 6 a.m. padding around the apartment trying to not make any noise. We pretended to not hear each other because neither of us wanted to share what we had. So we kept to ourselves.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

One morning in early summer, I woke to a furious knock at the front door. I closed one eye to look through the peephole and saw the landlord, Mr. Fowinkle, standing arms akimbo wearing a dingy oxford shirt and brown pants. His odd avian head peered back at me through the glass hole. He had these pea-sized eyes and a large nose that looked like it was pinched by an invisible clothespin. When I moved in, A. instructed me never to answer the door for him, seeing as how I was subletting the sunroom and wasn’t on the lease. So I never did. I stood there as he slid a yellow slip of paper beneath the door.

When she got home, I was panicking.

-We’re getting evicted?! Fowinkle slid this under our door today. Fourteen days!

-Huh, she said. That’s weird. Fowinkle is guano. Off the wick entirely. I’ll talk to him tomorrow.

-This isn’t about rent, right? I mean, I’ve given you my portion every month.

-Whoa! Why are you harping on me all the sudden? she said.

Her voice sounded brawny and absolute. She stood up straight.

-I said I’d talk to him! I’m the one who lets you live here, remember?”

-That’s not what I—

-Well I suggest you fence it in, sister. Fence it the fuck in, she said.

The eviction notice fell like an anvil on our friendship. I learned that A. had been pocketing all my money and using it to live on since she didn’t work. She had not paid Mr. Fowinkle a single cent in nearly six months. We had an ugly fight about it, much of which I didn’t understand, but I’m pretty sure that “guzzling kinsucker” was not meant to be a compliment.

I packed my things. I dismantled the cinderblock bookshelf and unstapled the bed sheets from the windows. I filled the milk crate with my books and I found a motel near the airport to stay in for a few weeks. It had a fuzzy television, an orange polyester bed, and a built-in ashtray on the bathroom wall. The ancient groundskeeper there, Mr. Jones, would ask me every day how my mother was. She’s fine, I’d say, How are you, Mr. Jones? And he’d throw his hands in the air and sigh, We here, aren’t we? We here.