Today was my annual check-up, and I was confident the doctor would confirm what I already suspected: I was becoming invisible. When I boarded the uptown bus, I was not at all surprised that the driver didn’t stop me and ask for the fare. It was no longer necessary to fumble in my wallet in a feigned attempt to find my NYC Senior Metro Card or pretend to forage in the bottom of my pocketbook for loose change. The driver wasn’t kind or lazy—he simply didn’t see me.

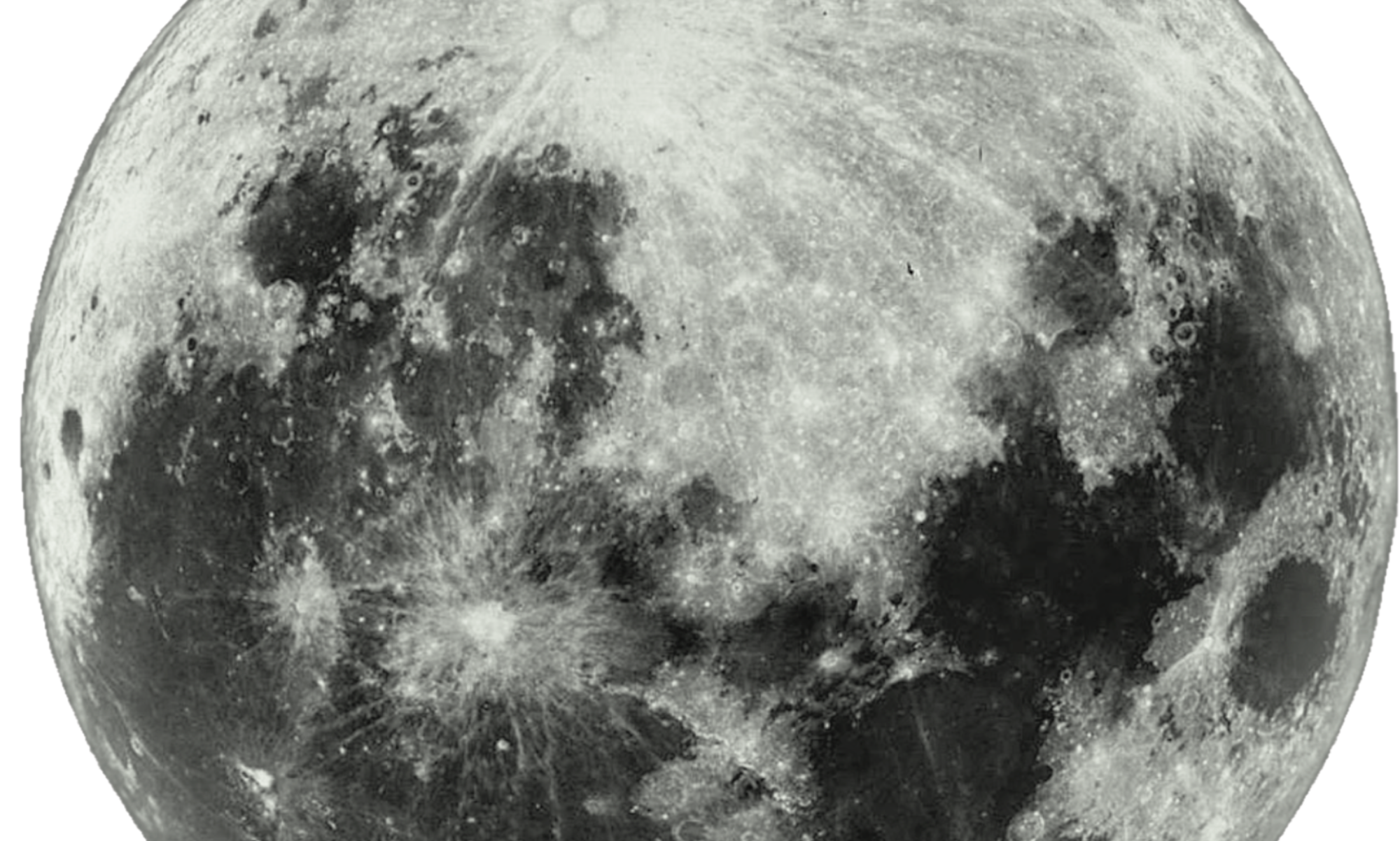

Bit by bit, body part by body part, I was disappearing. My hair, once a deep brown with red undertones, was losing its pigmentation. First, it turned gray, then white. Soon, it would be completely transparent. My skin was a succulent olive in my youth, requiring no creams or make-up. Now it looked like parchment. My hands barely concealed a tributary of blue snakes—awful to look at, but easy to prick for blood. The deep hue of my gray-green eyes was fading as my eyesight dimmed. Solid bones were crumbling, then dissolving. I was becoming a hollow-stemmed, leafless dandelion. Just blow on me, and I scatter in the wind.

The ride uptown was slower than usual. The bus stopped to pick up a passenger in a wheelchair. After the bus kneeled, the wheelchair scooted onto the ramp. Then the driver lifted the designated seats, shoved the wheelchair into the gaping hole, and strapped in the passenger. While it was usually interesting to observe, I was running late today, and I found the slowdown annoying.

“These changes are normal for your age,” said my doctor, who didn’t look older than fifteen. “All your vital signs are good. Your weight is normal. You haven’t lost any height. You could use some Vitamin D.”

“Then, why am I disappearing?”

He suggested I speak with a geriatric psychiatrist.

“Do you mean an old doctor or a doctor who treats old people?” I asked.

He looked flustered, and I immediately felt sorry. On my way out, the receptionist handed me some samples.

“Will these reverse the process?” I said. “I don’t want to disappear.”

“We’ll see you in one year,” the receptionist said with a nervous laugh.

As soon as I left the doctor’s office, I pulled out the red cashmere sweater I had stuffed in my tote bag and tied it around my neck to ensure that I would be spotted. Gone were the days when I walked into a restaurant, and the manager seated me immediately at a table near the front windows. Whether it was my height, which I exaggerated by wearing stiletto heels and piling my long dark hair on top of my head, or my mannequin-like beauty, I commanded attention and respect. Now, I had difficulty getting seated, even with a reservation.

Cynthia had already secured an outdoor table. The Broadway buses belched toxic exhaust fumes, but it was still better than sitting inside, where our conversation was drowned out by the cacophony of clanking plates and clinking glasses. The sound ricocheted off tiled floors and wooden tabletops and joined a chorus of people shouting: “Can you hear me?”

I waited until the waiter brought us our food and Cynthia had devoured her dish before making my announcement. “I’m becoming invisible.”

“Join the club. I’ve been invisible for years,” Cynthia said, as she swiped the bottom of the marinara-drenched bowl of pasta with a piece a garlic bread, making sure that every last drop of sauce got into her mouth.

“What are you talking about?”

“Ever since I gained the last fifteen men don’t see me,” Cynthia said. “You’re lucky you’re thin. And you never dieted, even when you were modeling.”

“Skinny genes, I guess,” I said and picked at my walnut-topped salad of kale and cherry tomatoes.

Cynthia was at least twenty-five pounds heavier than I was—twenty-five pounds more substantial, more important—not likely to become invisible anytime soon. We had been friends since childhood. Chubby as a child, Cynthia had blossomed into a full-breasted, wide-hipped sexy woman, but retained her old habit of eating whenever stressed. “Men prefer voluptuous women, look at pornography,” I said.

“Not so true anymore. Anyway, you’re the one who had tons of lovers.”

The men were interchangeable: Thomas, Bob, Ash, John, or maybe it was Jim. I was chagrinned to realize I couldn’t remember their names. Cynthia had joked that the men looked so much alike, I could use the same stock photograph that came inside plastic picture frames. The men bought expensive cast-iron pans that weighed more than I did and owned Viking ovens with red dials. But they preferred taking me out to restaurants—the trendier, the better—and made it their personal mission to put meat on my bones. The men had symmetrical features, good hair, and spray-on tans. What we lacked in natural passion, we compensated for with pot.

The men were the bounty of my modeling gigs. Cynthia had hooked me up with my first job, and it turned out to be a natural fit. For years, I oscillated between being looked at and looking; sometimes having my image captured by others, and other times being the observer, the chronicler, the artist. As I got older, the photographers stopped calling. Then, the art galleries lost interest in me. I had become invisible to them.

“Let’s go shopping after brunch. I need some new clothes,” Cynthia said.

“Aren’t you going to Debra’s art show opening in Soho?”

“Naw. I helped her mount her paintings, and I’m seeing her this weekend.” Cynthia scraped her now empty bowl with her fork and looked up frowning. “Why don’t you join us? It’s been a while since you’ve gone upstate.”

Four fellow artists had chipped in and purchased an old barn before it became chic and unaffordable, and transformed it into an art studio and an escape for those who lived in cramped city dwellings and craved unobstructed natural sunlight. We brought sleeping bags and camped out on the wide-planked wooden floors, never having enough money to install plumbing or heating.

At first, I was captivated by the unfamiliar eye candy of the country. Every season brought with it different shapes, textures, and a new palate of colors. The barn abutted a large meadow that was overgrown by dandelions. Twice a year, in the spring and then again in the fall, the dandelions morphed from tall-stemmed, canary-yellow leafless flowers to fuzzy balls of white, airy seed-heads that floated like little umbrellas from just the slightest breeze.

As much as I loved the country, it didn’t take me long to realize that I couldn’t work there. The stillness suffocated me and atrophy set in. I needed the chaos of the city to recharge my energy and release my creativity.

Today, after brunch, I left Cynthia at the corner. She headed over to Bloomingdale’s, and I hopped on the downtown bus to Soho. The gallery was packed, and Debra was talking-up prospective buyers, so I meandered around the room, making loud, animated comments in front of each painting. From the corner of my eye, I spotted a tall man holding court, surrounded by a ring of men and women. Even though he looked familiar to me, I was not going to join his orbit. I stood in front of a painting and waited.

“Hello, Scarlett,” he said, tugging at the edge of my sweater. “Friend of the artist?”

“Yes,” I answered, and turned around, so I faced him. “I’m C.C.”

He was well-built, with gray sprinkled throughout an abundance of coal black hair. His dark eyes were heavily lidded, and his nose was so large it looked like it was going to fall off his face. It surprised me when he spoke without an accent—he looked foreign, almost exotic to me.

“I’m Roy,” he said and extended his arm.

I stuck my hand in my pocket, not eager to reveal what was under the surface.

“We’ve met before,” Roy said. “At a MOMA fundraiser.”

“I don’t …”

“I’m a fan. You’ve elevated the art form of collages to a new level,” Roy said, as he threw out his arms. For a moment, I was afraid he was going to hug me.

“Thank you.”

“Have you seen my work?”

“I’m not sure.”

“I guess I’m not that memorable,” Roy said with a wide smile. Then he pulled out a business card. “I’m showing next week. I hope you can make it.”

As I took the card, his hand briefly grazed mine, and I suspected he lingered just a moment longer than necessary. Then he turned around and walked away—a walk that landed somewhere between a swagger and a wiggle—and rejoined his entourage. Once in a while, I shot a look in his direction, penetrating his protective circle, and caught him staring at me.

I left the gallery and hiked home. When I arrived, I glanced in the hallway mirror and noticed that my cheeks were slightly rosy—pink wash over alabaster. Apparently, the walk had done me some good.

The following week, I went to Roy’s art show. His paintings were bold, vibrant, and bursting with clashing colors: the red of Rothko, the purple of O’Keeffe, the yellow that drove Van Gogh mad.

When Roy spotted me, he rushed over and gave me a quick hello. “You came. Thank you.” Then he darted through the room with the same manic energy that was reflected in his art but returned to me every ten minutes or so. I knew how difficult that must have been for him; he needed to circulate and sell. “Don’t worry about me,” I said. “I know what it’s like.”

“I’d like to see you again,” Roy said. “Tomorrow? I’ll meet you wherever you want. Or I can pick you up from your place or come to mine.”

His eagerness amused me. When I didn’t respond quickly, Roy jumped in. “Okay, then, my place.” And he scribbled his address on the back of his card.

“Hmm. Not your usual type, but he’s a good guy.” Cynthia said when I asked her about Roy. “I’m surprised you aren’t familiar with his work, he’s quite popular.”

Roy’s living room was painted in at least four coats of bisque, resulting in richness you could almost taste and adorned with large pieces of his artwork. The kitchen was tiled subway-style in black and white with touches of turquoise. Every possible gadget sat on the counter-top, including a bagel slicer.

“I’m a great cook. Maybe one day, you’ll let me cook for you,” he said.

I unsuccessfully suppressed a laugh. Was my thin body a magnet for men who wanted to feed me? Did they all want to fill me up?

When he gave me a tour of his apartment, I spotted a few dark canvases stacked against the walls of the spare bedroom.

“I’m preparing a show, a fundraiser,” Roy said.

“Not your – “

“No. My younger brother was also an artist.”

“Was?” I asked.

“When Gary came out, our father threw him out,” Roy said. “He lived with me until he died.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“The visitors stopped coming, even though they knew, we all knew, it wasn’t contagious from everyday contact. Gary just disappeared. Piece by piece. Slowly, then not so slowly.”

I didn’t know what was more unsettling—what he had just revealed to me, or the ease with which he had peeled off a layer, so early in our fledgling relationship. Roy had shifted into automatic—repeating a story I assumed he had told to many people. “He wanted to be remembered for his art, not by a stone. ‘Don’t bury me in the earth,’ Gary said. ‘I can’t paint in the dark.’”

Then, as if some necessary prerequisite had been met, Roy leaned in and kissed me. I jerked away. Too soon. Too easy. I guess men had not changed that much over the years. Exchange a quick, revealing intimacy—abused by dad, ignored by mom, a recovering whatever—and zoom in for the kill.

“Sorry. I’ve been told I can be impulsive. Let’s go out for dinner, okay?”

Thus, began two months of dating Roy platonically. He didn’t touch me or try to kiss me again. It was quite a change. I was accustomed to men coming on to me. Cynthia thought it was because I was thin, but the real reason was that I didn’t give a damn. Men seemed to like a challenge. My nickname—Icy C.C.—was well-earned. And though I had many lovers, I had never been hurt. But I had paid a heavy price for my protective casing—after numerous affairs, I was still a virgin in one respect—my heart was intact.

As Spring eased into Summer, Roy and I behaved more like girlfriends than potential lovers.

“I hate my nose,” he confided. “It’s the first thing people see.”

“I like your nose,” I lied. “And your wiggle.”

“Hip replacements,” he shot back. “And you, my dear, you’re so perfect. Do you even have a body part you hate?”

“My breasts,” I said, and tried not to look down.

“Ah! Remember what the French say: more than a mouthful is a waste.”

“O-kay,” I said frowning. Roy came dangerously close to crossing that bright red line that separates friends from lovers, and friends were far more precious to me.

Roy plowed on. “Fifteen years ago, doctors found a small aneurysm and inserted a stent. No problems since then, but the procedure left a scar—like someone had drawn a line with a number two pencil. Do you wanna see?”

I resisted the temptation to look.

Over the summer, our mutual respect deepened. Roy was a powerful, but untamed, creative force, and I helped him prepare for his art shows. Roy encouraged me to make more collages, fascinated by my ability to cut apart old magazines and reassemble the pieces into portraits and city landscapes: the sidewalk fruit vendors on Amsterdam Avenue selling puckered-skin oranges and speckled bananas, the father and son hawking shiny, gray fish straight from the Fulton Fish Market, a toothless man playing speed chess with a teenager in Washington Square Park. My camera captured the initial image. Then, I blocked out the shapes and colors on oaktag, and from my collection of cut-up magazines, selected the pieces I would use. Roy took his favorite collages of mine and hung them in his latest show, and the demand for my work increased.

We both supported liberal causes and stayed up late drinking wine and fixing the world’s problems. Though our banter veered from the mundane to the wise, from the impersonal to the flirtatious, our relationship remained chaste.

As a result of Roy’s abstinence, I relaxed in his presence, but at the same time, I was drawn to him physically. More and more, I sought out body contact with him—pressing against him as we sat and watched a foreign film; looping my arm through his as we walked in Central Park; looking forward to the perfunctory hugs we exchanged when we met and parted; holding onto him just a moment longer than necessary. Slowly, my hunger for him grew.

Very quickly, it became apparent that Roy was a person of superlatives. He was unusually happy, almost to the point of being silly, and very appreciative since the death of his brother. Every day was a gift. Every piece of food—every sunrise, every flower, every walk—was the best. And while he could be impulsive, he was so patient with me. I began to wonder if he still found me attractive.

One thing had not changed. Though random bursts of color graced my cheeks and lips, and my hair seemed fuller, I was still becoming invisible. The process had not been reversed by the long hikes where my lungs almost burst from sucking in the fresh air, or the gourmet meals Roy prepared for me, or the surge in my creativity.

One day, in mid-summer, we walked through the park for hours. Roy had brought his old Polaroid camera and took photos of the trees and bushes bursting with new buds. A late afternoon shower caught us by surprise, and we ran—giggling like young lovers from a French film—to his place. When we arrived, he taped the photos to the top of his easel, and I stood behind him as he applied thick strokes of chartreuse and pink onto the canvas, his broad shoulders straining against his shirt, still wet from the rain. When I lightly brushed up against his back, he spun around and grabbed me. This time, I was ready to receive him.

Afterward, we stood side by side in the kitchen as he cooked dinner. I wore one of his tee shirts, swallowed up by its size, and watched him chop onions, baby bok choy, and sweet red peppers, then throw everything into a wok with some chicken he had been marinating with soy sauce, chunks of ginger, and cloves of mashed garlic. I was so famished I had seconds.

Roy’s enthusiasm was contagious. He made me laugh—from the bottom of my stomach— like a child, who hasn’t learned it’s impolite to show your feelings, the kind of laugh where your make-up runs down your cheeks, and your nose runs, and you don’t give a damn. After years of worrying about my appearance, I no longer cared about how I looked. It was a good thing I was becoming invisible.

“You look great,” Cynthia said, as she studied the menu of the new café she had selected.

“Hadn’t noticed. Not that there’s anything left to see.”

Cynthia squirmed, never quite sure if I was joking. “Someone wants to buy the barn. Really only interested in the land. He’ll probably tear down the barn.”

Even though my trips upstate had become infrequent, it was still unsettling to hear.

“Let us know if you object,” Cynthia said.

“No. I’m fine with it.” I couldn’t do anything about it, even if I wanted to.

“Some of your oils and collages are there. Decide what you want to do with them.”

Roy convinced me to make a weekend out of it, stay at a B & B, troll for antiques, look at Hudson Valley art, take photos.

“Wow. This property is beautiful,” he said when we pulled up to the barn. I could live here. Take long walks. Paint. Chronicle the change of seasons from the same vantage point.”

“The barn is not winterized, and there’s no plumbing.”

“We could install baseboard heating, dig a septic tank, build a kitchen, put in bunk beds—”

“Whoa! Slow down.”

“Buy out Cynthia and the others.”

“First, I have to find out how much—”

“Money is not a problem,” he said.

Only when we were on the road, headed home, that I realized we had left some of my collages in the barn.

“I guess we have to come back,” Roy said, barely concealing his grin.

It was the first of many long-term plans. Paris in the Summer. Portugal in the Fall. Ireland for the green. We both had the golden handcuffs of rent-controlled apartments and were not in a rush to move in together. We could make our own rules, set our own course.

Roy set up an old drafting board in his spare bedroom. He drew up some blueprints, and I moved around little pieces of oaktag I had cut out to represent furniture and appliances. After only a few days, our plan seemed to be coming together.

“Let’s go upstate tomorrow. I need to take some more measurements,” I said, surprised at my own enthusiasm.

For the first time, it was Roy who slowed us down. “It’s gotta be next week. The doctor said I need a tune-up on my stent.”

“You’re having surgery?” I asked, suddenly feeling cold.

“It’s not surgery, just a procedure.”

“What’s the difference?”

“I’m not sure. But I’ll be home the same day.”

But Roy didn’t come home that day. Or the one after that. The medical workup for the procedure revealed a new, unrelated problem. One day morphed into two days, then two weeks. Soon it was clear that Roy was not coming home.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

The nursing facility smelled like the inside of an NYC taxicab. I was assaulted by the mix of urine, ammonia, and the overly sweet scent of pines, like the cardboard Christmas tree hanging on the cab’s rearview mirror. I met Roy in the dining room.

“Come join me for lunch. It’s not half bad when you get used to it,” he said, looking down at his puréed vegetables.

His plate looked like a child had just finished finger painting and had mixed up all of the colors into a muddy brown. Glancing around the dining room, I realized that everyone’s food was puréed. I fought down waves of nausea.

“Maybe you could sneak in some herbs and spices from my kitchen,” Roy asked.

“Sure. The people at the front desk don’t see me, anyway.”

When I arrived at Roy’s place, I rummaged through his kitchen. Because Roy had been the cook, I had never paid much attention to what went into his creations. There were veggies in the fridge and pieces of chicken in the freezer. Roy’s recipes were written on three by five-inch index cards and kept alphabetically in a little metal box that sat on the counter. I rifled through the cards; on the bottom right of each handwritten recipe was either a smiley or frowny face. Roy had rated them according to whether I liked them or not—an unexpected system from an unsystematic person. The recipes, however, contained no measurements. Roy had described the required amount of an ingredient by the color and texture it produced when cooked: sprinkle enough paprika to turn the crust into a deep sienna; slowly add corn starch until the sauce shimmers like Bermuda sand.

I pulled out a recipe that used the ingredients on hand and decided to give it a try. As the familiar aroma wafted up, the memory of the first time Roy had prepared that same dish for me swept over me. It surprised me to feel tears stinging my eyes—probably from the onions. Next time, I would run cold water over the onions, as Roy always did. I put the finished product in a blue and white Pyrex dish and covered it with Saran Wrap.

On my way to see Roy, a woman in a wheelchair got on the kneeling bus I was on, looked right at me, and smiled. Her smile was inexplicable to me. Dark hair framed what had once been a pretty face but was now ravished by disease. I hope she’s not in too much pain, I thought.

When I handed the dish to Roy, a smile leaped off his face. “You cooked for me. I can’t believe you cooked for me. Let’s go to the dining room.”

“It’s only ten.”

“You should know by now; patience is not one of my virtues.”

The following morning, feeling empowered, I walked to Roy’s place and pulled out a more ambitious recipe. I didn’t have all the necessary ingredients, so I sprinted to the nearest grocery store. When I threw some fresh dill and Italian parsley into my tote bag, a clerk stopped me.

“What are you doing?” he shrieked.

“I’m not stealing. I always shop this way. No one ever stopped me before,” I said.

“Use a basket, lady. Use a basket,” he said, dragging his right foot as he limped away.

How sad, I thought. He’s so young.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

By late summer, Roy was eating his meals on a tray in his room, but today he asked me to wheel him into the dining room. Sunshine streamed in and exposed the grease-streaked forks and glasses. I stifled my temptation to ask an aide to replace them. Roy ate the food with so much gusto I was sorry I had not prepared more. I held back my tears until I was out of sight.

Two weeks later, I called Cynthia and asked her to meet me for brunch.

“You put on some weight,” Cynthia said.

“Not really.” I looked down and wadded my paper napkin into a ball, not quite sure how to proceed.

“Is something wrong?”

“I’ve been cooking for Roy.”

“You? Cook? It must be love,” Cynthia said as she grabbed a large chunk of focaccia from the bread basket and dunked it into the dish of herb-infused olive oil.

There was no easy way of broaching the subject with Cynthia. “He needs me. He’s really sick.” It was the first time I had said the words out loud, and they sounded harsh and irrevocable, like words carved onto a headstone.

Cynthia stopped eating, reached across the table, and touched my arm. “I’m sorry,” she said. There was nothing else to say.

On the way home, I walked by the doorway of a church and a man, sleeping on a filthy mattress covered in oily rags, nodded at me. Must remember to bring him some food, I thought and returned his nod.

Cynthia had given me her favorite recipe. The list of ingredients was intimidating: orecchiette, white beans, bacon, rainbow chard, fresh thyme, Parmesan cheese. Not for the faint of heart. I was giddy from anticipating Roy’s reaction.

Dish in hand, I entered the nursing facility, but for the first time, the receptionist stopped me. She looked down at my Pyrex dish, and a look of fatigue crossed her face. “He’s been moved to the fourth floor, Cecilia. He requested a window.”

Roy was lying on his back—like a deflated balloon—his large nose thrust in the air. I approached him cautiously—fearful I might float away. But with each step I became stronger and more sure-footed. When I leaned over to kiss him, he lifted one hand and traced a line down my cheek with his thumb.

“You came. Thank you,” he said in a hoarse whisper.

“I made you a new dish,” I said and placed the bowl on his tray, next to the water pitcher and Styrofoam cup of shaved ice.

“Sorry. Can’t eat,” he said and slipped into a morphine-induced twilight sleep.

Tears blurred my vision. Roy’s body parts came flying loose, joined by tubes, glucose bags, and IVs. I blinked hard, trying to clear my eyes, trying to force everything back together again. The pieces were all there, but had been torn apart and couldn’t be reassembled.

Roy opened his eyes, and his initial look of confusion melted into the peaceful, pain-free face of a child. “Cecilia?”

“I’m here,” I said.

“You sure are.” And he smiled so faintly it was almost imperceptible.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

Alone, I took the long bus ride to upstate New York to retrieve my collages from the barn. It was a brisk, late-fall day. I walked out into the meadow. The air was thick with the swirling white clouds of liberated dandelions. I threw a handful of dust into the air where it joined the dandelions and scattered in the wind.