Jordy and I floated on our backs in the spring-fed lake, while a cool drizzle settled on our tired bodies. It had been a long, sleepless August.

“Thanks, Mom,” he said, his twelve-year-old voice still small, un-deep.

“For what?”

“For bringing me here.”

“Sure.”

“And not thinking I’m crazy.”

“About the cricket?”

“Yeah.”

“No problem,” I said. I didn’t think he was crazy. He was grieving. The mind does funny things when someone you care about disappears in the middle of the night.

I moved my arms through the water, stretched my legs toward the bottom. Feeling nothing, no lakebed, my heart dropped. We had drifted. I kicked toward the shore until I was close enough to feel the firm wet sand beneath my toes. Jordy floated around me in circles. He’d always been a good swimmer. Adam had taught him.

“You don’t think Dad’s coming back this time?”

“No. Not this time.”

“How do you know? Did he say anything?”

“No.” I was glad my son wasn’t looking at me. He was tan and lean and his brown wavy hair was so much like his father’s. The truth hadn’t changed. Adam was gone and was staying gone. It had been over a month.

“But you believe me?”

“About the cricket?” Did I believe a cricket came to his windowsill every night, chirping to Jordy when he couldn’t sleep? Hell no. “I’m not sure it’s the same cricket.”

“It is. I know it.”

He was getting a little old for such tales. I worried that he was regressing into some childhood state from the good years, when his father was healthy.

The drizzle thickened into a downpour. We trudged from the lake and dashed to the old minivan. After wrapping up in fluffy yellow towels, we dug into the paper grocery bag for snacks. Gobbled peanuts from the jar. Jordy opened the cooler and handed me a cherry Coke, took one for himself. Sheets of rain cascaded across the empty beach.

Later, at home, the rain gathered into a thunderstorm, and we sat on Jordy’s bed, reading books after dinner. I kept the window cracked open. Jordy’s bed was next to the wall, which Adam had painted sage green. I leaned against it, remembering when Adam had let himself lean on me. I craved a different memory, one of me leaning on Adam. I could never find one, though I imagined what it would have been like to have him hold me and tell me everything would be okay.

I later woke into darkness with Jordy curled up next to me, a tangle of limbs. The rain had stopped, and August humidity panted into the room like dog breath. The night was hushed, until the cricket chirped. I jumped.

“It’s him,” Jordy whispered.

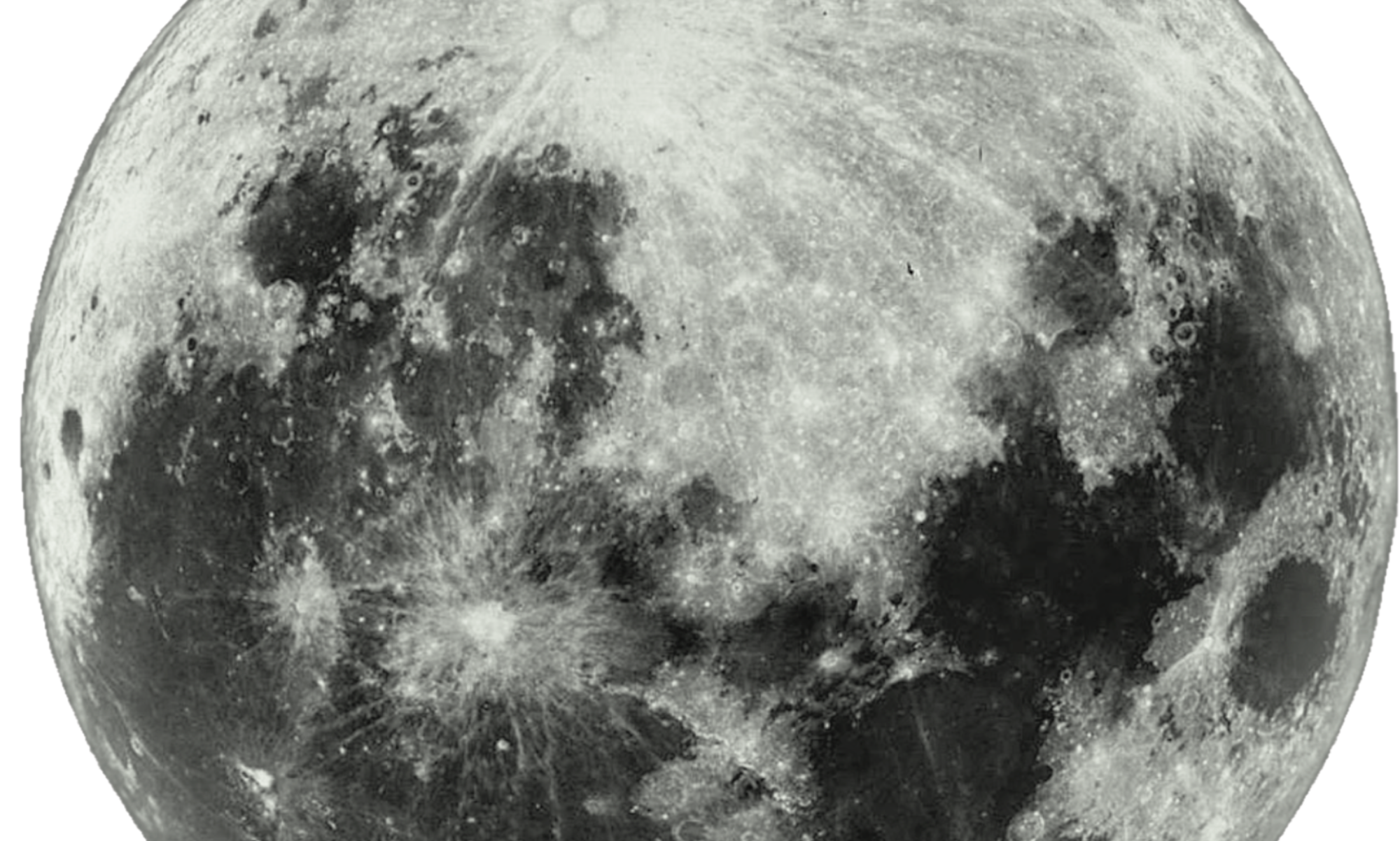

The cricket was on the other side of the screen. In the moonlight, this slick thorax gleamed like molasses. We listened, until Jordy fell asleep, and I crept to my bed. It yawned at me, empty and cold.

For the next few nights, I tiptoed into Jordy’s room after he had fallen asleep. Then the cricket would chirp, and Jordy would stir. I was entranced, standing silently in the doorway. Listening.

One night, I appeared in my usual spot and leaned against the doorframe. Sleep eluded me on a regular basis, but Jordy’s cricket could chirp me into a restful state. Hearing the gentle song, I was able to push away thoughts of Adam. I had loved him through his darkest, most depressed days. But when things got worse, I asked him to try a new counselor, or a different medication. Didn’t Jordy matter? Didn’t I? Instead, Adam left, as he had twice before. This time, there was a note. I can’t do this anymore.He wasn’t coming home. The knowledge had rooted inside of me.

“Mom? Are you there?” Jordy called from his bed.

“Yeah, sweetie. I hope I didn’t wake you. Just waiting for your cricket.” I believed now in the magic of it, that it was the same cricket, returning to the sill every night, because we needed him to.

“He’s gone.”

“Gone?” I asked. I walked across the room, sat by Jordy’s feet.

“Don’t be mad,” he said.

“Why would I be mad?”

“I did something.”

“Tell me.”

“I ate him.”

“What?” The room was stifling suddenly. “You didn’t.” He couldn’t have.

“I didn’t want him to leave, Mom. Not ever. I’m sorry,” he said. Moonlight shone through the window. Jordy was sitting up now. He hung his head. “Did you ever do anything like that?”

I didn’t want to answer, didn’t want my son to know what I had devoured the weekend after Adam left, and I’d sent Jordy to my sister’s. The grief, the rage, that would not drown in gin, that would not dissipate under the weight of the man I’d brought home from the bar, that could not be scrubbed away after I’d vomited the gin.

I said, “After my godmother died when I was eight, my dog killed a sparrow behind our house. He didn’t mean to. I kept the sparrow in a shoe box in the garage to look at. My father found it and made me bury it.” It wasn’t the same. My hands shook as my thoughts tendrilled into the future to see my son full-grown, staggering under the weight of unspoken grief, like his father. And me, old and hovering, and still not enough, for either of them.

I saw him nod. “So, you’re not mad? You understand?”

“Oh, Jordy.” I hugged him tightly. “Yes, I understand.” I tried not to cry but I did, my tears soaking into his t-shirt. I was so afraid, and it was frightening Jordy, but I didn’t know how to stop.

I ached for the cricket song, the illusion of magic, the pretense that he was there to soothe us, that Jordy was okay, that I was.